ARTICLE AD BOX

A new coronavirus variant is sweeping through Europe and the United States as officials advise ramping up monitoring of its spread.

The variant – known as XEC – has infected 600 people across Europe and North America just ahead of the winter season in the Northern Hemisphere, during which respiratory diseases are typically more widespread.

The variant appears to spread more easily than previous types of COVID but cases of the infection have not been as severe as those seen during the peak years of the pandemic.

So what is different about XEC and is there cause for concern?

What is the new COVID XEC variant?

XEC is a “recombinant” version of SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that caused the original COVID-19 pandemic.

Recombinants form when a person is infected with two different strains of COVID at the same time. Genetic material from the two different strains then “recombines” or “exchanges” with each other, creating a third, new strain.

While symptoms from XEC have so far been reported as mild, the new strain is part of the “Omicron” lineage – a more severe variant of coronavirus which peaked in 2022.

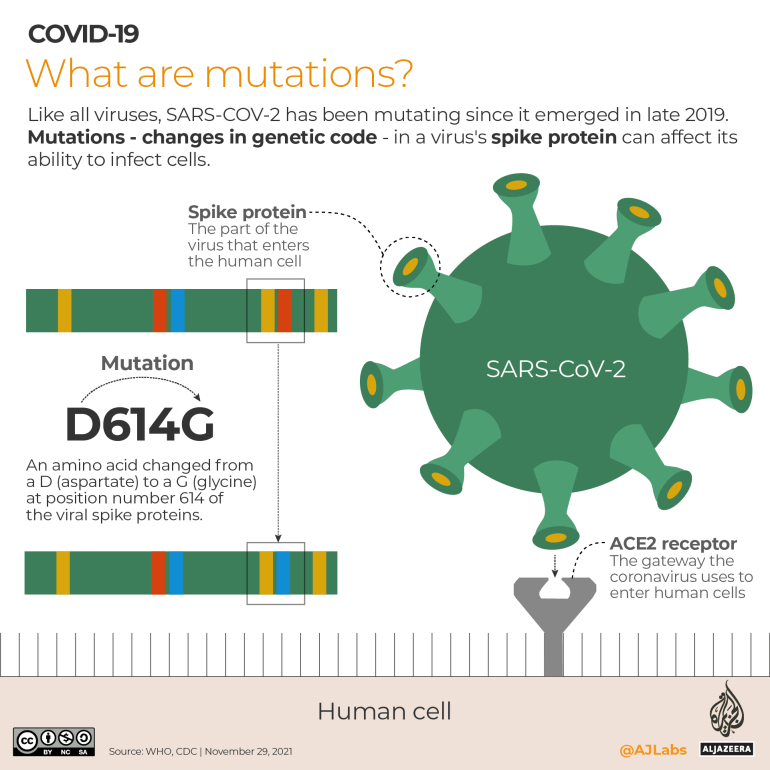

Each variant or strain develops mutations which are characterised by different “spike proteins” on the virus. These proteins are what bind to human cells, allowing the virus to enter and start replicating inside the human body.

Over time, Omicron has developed its own offshoots or subvariants. Two of these – KP.3.3 and KS.1.1 – are the two which have recombined to form XEC. They are closely related and evolved from the earlier JN.1 variant, which is also part of the Omicron lineage and was dominant around the world in early 2024.

Recombinant variants are not new. The XBB recombinant variant dominated COVID cases in 2023.

Al Jazeera

Al JazeeraHow does XEC spread?

Like other coronavirus variants, XEC is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets that are suspended in the air when an infected person breathes out, talks, coughs or sneezes. While the virus can survive on surfaces, transmission through this route is less common than airborne spread viruses.

Therefore, public health officials are advising people to socially distance, wear masks in public spaces and use hand sanitiser.

However, XEC, it is believed, can spread even more easily than previous COVID variants. This is due to its particular spike proteins which may allow it to enter cells and multiply more easily. The exact nature of its transmissibility is still being studied.

What are COVID XEC symptoms?

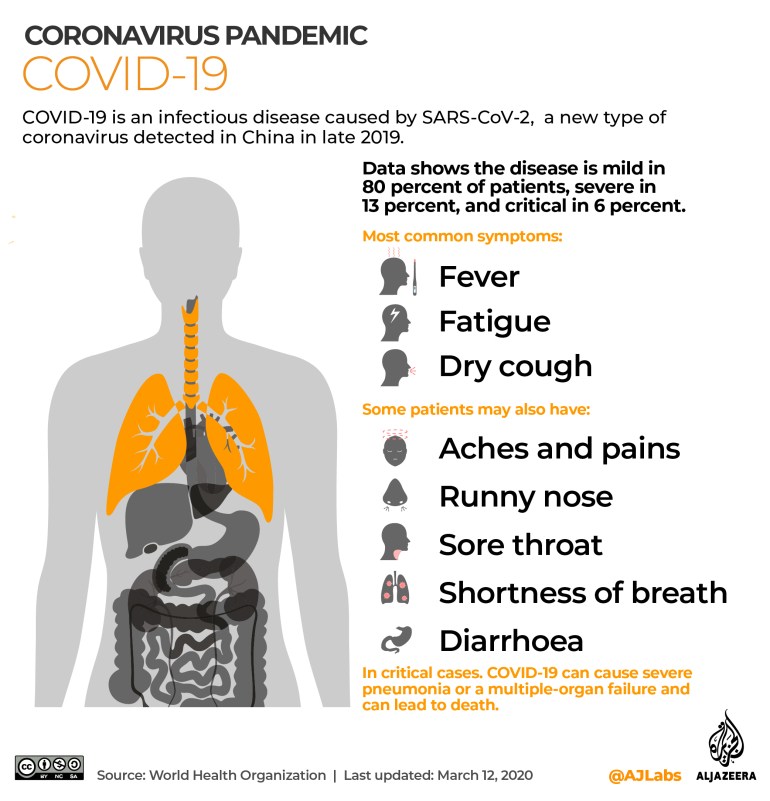

XEC can cause symptoms such as a sore throat, fever, fatigue and muscle aches. These are likely to be mild and will appear after two to 14 days of infection. The severity of symptoms varies. Cases may be more severe in high-risk people such as the elderly or can be completely asymptomatic.

So far, XEC is not known to cause any unique symptoms or more severe effects than other COVID variants.

When was the new strain detected?

XEC was first detected by researchers in Berlin, Germany, in August among COVID-19 samples collected two months previously.

The sample collection in June was part of routine COVID-19 surveillance in which genetic material from nasal swabs of infected people is sequenced or analysed.

It is not clear why there was a two-month delay in detecting the variant but in many cases, this can be due to sequencing backlogs, especially if the focus was initially on other dominant variants at the time.

Where has it spread so far?

Since then, more than 600 cases have been reported in 27 countries across Europe and North America, according to a tracker maintained by the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). The organisation is based in Munich and run by independent scientists from around the world.

More than one-fifth of the cases (21 percent) have been discovered in France, where it is most widespread. However, it is also gaining traction in the United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany.

In the United States, more than 100 cases have been reported in 25 states.

However, the actual global spread of XEC may be larger as not all countries routinely report data to GISAID, according to Bhanu Bhatnagar at the World Health Organization (WHO) regional office for Europe.

How dangerous is XEC?

Evidence so far suggests that XEC is not a radically different or more dangerous variant than other Omicron subvariants of COVID.

Unlike several new variants in the past, such as JN.1, the WHO has not categorised XEC as a “variant of interest” yet.

As with other respiratory viruses, COVID-19 and its variants are expected to spread more during the autumn and winter seasons of the Northern Hemisphere as people spend more time indoors in closer proximity to one another and with less ventilation.

Mike Honey, a data visualisation and data integration specialist based in Melbourne, said in a post on X that he expects the variant to peak in late October or November mainly in Europe and North America.

Additionally, initial studies show that existing vaccinations are sufficient to protect against the XEC variant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US has recommended that anyone aged six months and over should receive an updated 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccine to protect against the virus, even if they have previously been vaccinated against COVID.

3 months ago

67

3 months ago

67

English (US)

English (US)